While plunging output in Venezuela captures the oil world’s attention, problems are quietly festering in another Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) nation.

Angola, once Africa’s biggest crude producer, is suffering sharp declines at under-invested offshore fields, with output dropping almost three times as much as the nation pledged in an accord with fellow OPEC members.

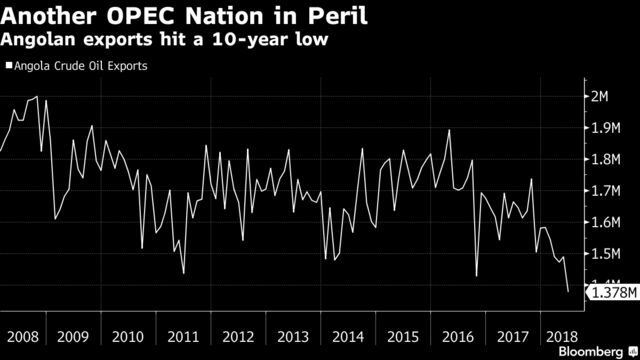

With the losses set to accelerate — a shipping programme seen by Bloomberg News shows crude exports will fall in June to the lowest since at least 2008 — the cartel risks tightening supply too much.

“Angola has a serious problem, with its decline rates becoming increasingly visible,” said Richard Mallinson, an analyst at consultants Energy Aspects Ltd. in London. “The low figure in June doesn’t look like a pattern of maintenance but points to steeper, structural declines.”

Output interruptions among the organization’s members could send Brent crude prices above $80 a barrel, Bank of America Merrill Lynch analysts including Francisco Blanch, head of commodities research, said in a note to clients.

Unintended supply disruptions are rife in the cartel. Nigeria and Libya were exempt from the deal to cut output because their production had already been diminished by local instability, while Iraq’s implementation of the accord only improved after a political dispute halted exports. Some traders are already shunning Iranian crude in fear that President Donald Trump will re-impose sanctions.

Alleviating Decline

Angola’s slide could be alleviated by the end of the year, with the start up of an oil field operated by Total SA. The Kaombo field, delayed from 2017, will have a capacity of 230,000 barrels a day.

That might not come soon enough.

Although output from all oil fields diminishes over time as the pressure in their reservoirs falls, Angola’s deep-water operations are especially costly to maintain. Because of insufficient capital expenditure, the rate of decline from Angola’s deposits is more than double the global average, at 13 to 18 percent, Mallinson estimates.

“Most Angolan fields have struggled or entered into a steep decline phase after three years — it’s the nature of the geological characteristics of Angola’s offshore production,” he said.

The country’s struggles will only intensify in coming years, the International Energy Agency predicts. Since peaking at 1.9 million barrels a day in 2008, Angola’s production has slumped to about 1.5 million, and will dwindle to just under 1.3 million barrels a day in 2023, according to the agency.

.Bloomberg